“That’s the thing about faith… if you don’t have it, you can’t understand it. If you do, no explanation is necessary.”

-Kira Nerys

The Roman Catholic Church: one of the longest standing hierarchies in Western civilization. It’s only natural that writers, filmmakers and storytellers are inspired by the Church to create their own religious structures — and it happens more often then you’d think. This periodic series will chronicle the many kinds of Space Catholics, their view on clericalism, sacramentality, sin and more, and how close — or how different — they get to the real thing.

THE BAJORANS from STAR TREK: DEEP SPACE NINE

The Bajorans are, quite possibly, one of the best examples of Space Catholics, sporting a stratified clerical structure, active canon law and moral authority.

God: In Bajoran faith, “God” is represented by the mysterious “Prophets” who watch over Bajor, impart their teachings, and protect the Bajoran people from harm. For most ordinary Bajorans, they are considered divine beings, although the heroes of the series discover them to actually be super-advanced alien living in a local wormhole. This shocking news does not quite dissuade Bajoran worshippers, who choose to continue their worship and study of the Prophets and their works unabated.

Pope Winn I.

Pope Winn I.

The Pope: The Kai, the Bajoran spiritual leader, is elected by the Vedek Assembly — a council of high-ranking Bajoran clerics — for a life term. Bajorans are encouraged and accepted to follow the Kai’s religious teachings. Although the Kai does not put out encyclicals, his or her words are still politically important in much the same way as the Pope’s words matter to our world; there is no direct Vatican cognate, but it’s intimated that before the Cardassian occupation that Bajoran secular politics was influenced by the needs of the Kai and the Vedek Assembly, much like medieval kings’ relationship with the medieval Church.

The Bible: In Bajoran religion, the words of the Prophets are considered sacrosanct. As in Catholicism, there are various levels of translation and interpretation happening, from those who believe the Prophets words should be taken extremely literally, to those who spend their lives in interpretation; however, like Catholicism, there is a distinct code of canon law; like medieval Catholicism, it sometimes also stands in for secular law. Ordinary Bajorans have a faithful, pragmatic view of their faith and the role of the Prophets in their own lives that echoes modern Catholicism very well; many of the character Kira Nerys’ statements about religions and faith can be exchanged word-for-word with those of modern Christianity and not need to change, while other Bajorans are entirely secular or take a more violent, jihadist tack, such as when extremists blew up a school on the space station.

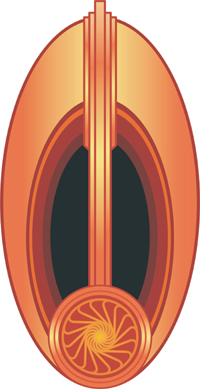

The Orb of Shininess.

The Orb of Shininess.

Relics: Orbs, called the “tears of the Prophets,” are centers of worship for Bajorans and function in much the same way that relics do for modern Catholics — as channels of prayer, understanding, worship and contemplation. They provide measured and definitive miraculous experiences, such as visions and healing.

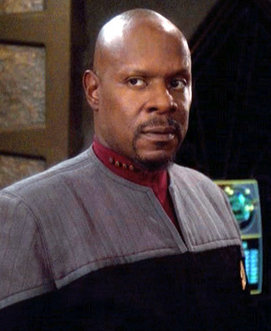

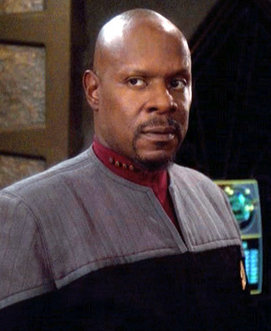

The Emissary was not actually Bajoran.

The Emissary was not actually Bajoran.

Jesus: This isn’t a direct cognate, but the Bajorans have a concept of “The Emissary,” a personage who would save Bajor; this figure, the character Benjamin Sisko, eventually fulfulled Bajoran prophecies by sacrificing himself for the Bajoran people. Like Jesus, he is assumed bodily into “heaven,” or the Bajorans’ “Celestial Temple.” Unlike Jesus, Sisko is fully human. Like Jesus, he was “in the world,” i.e., the entire galaxy, but “not of it,” i.e., Bajor and the Bajoran faith in particular.

Contemplative Orders: Most of the Bajoran clerical structure seems to be made up of monastic intellectuals attempting to find some way to interpret and understand the Prophets’ words.

Clericalism: A direct lift. Prylars are monks, ranjens are priests, vedeks are bishops and kais are popes.

Spoiler! Not actually Bajoran, either.

Spoiler! Not actually Bajoran, either.

Holidays: during the Bajoran “Time of Cleansing,” people fast and pray, and abstain from sin. This is a cognate more to Ramadan than Lent, but it still counts.

Gender: Gender does not seem to matter to the Bajoran religious hierarchy; vedeks, Kais and regular monks are woman and man, married and single, chaste and parental.

The Devil: The pah-wraiths are Prophets from the same race who long ago willingly gave up on the path of peace, much like Lucifer rejected God.

– – –

Support Sacred Earthlings by purchasing this or anything else from our Amazon affiliate link: